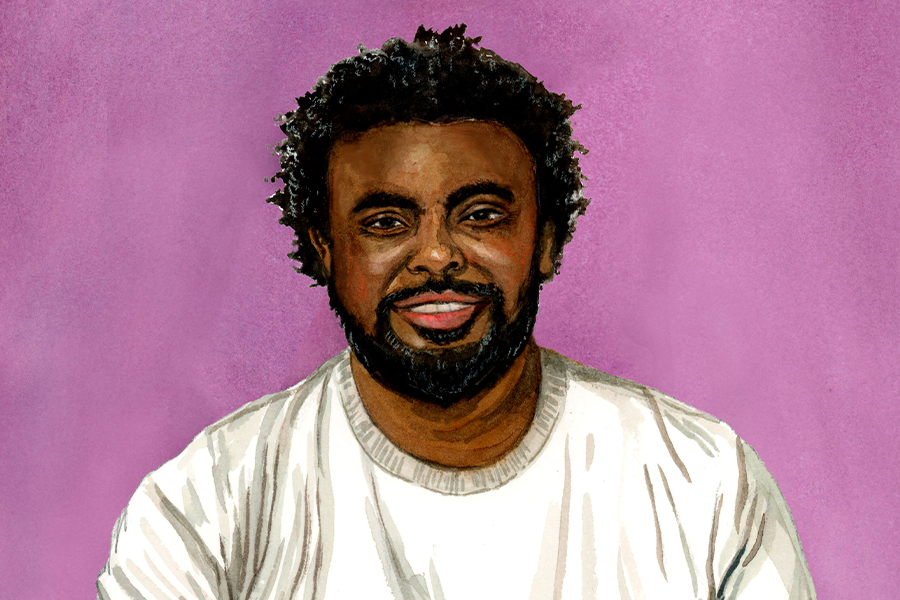

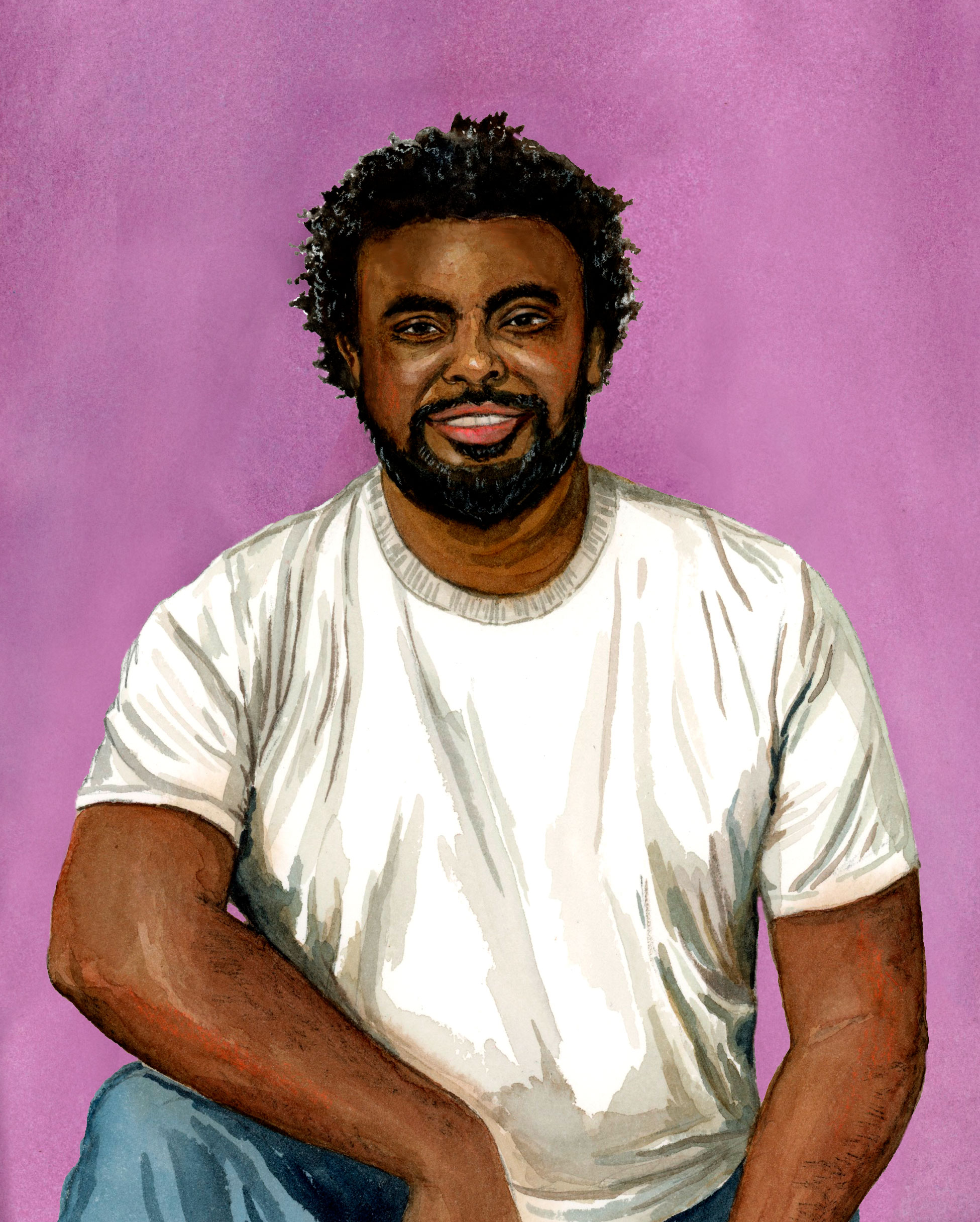

“We’ve been declined, overlooked, deprived of, boxed in, and relegated in so many corners of our lives.”

Marcus Bullock is an entrepreneur through and through. As a child, he sold candy on the school bus, making a ten-cent profit on each sale. He stayed out of trouble and focused on school. But as he grew older, he aspired to take his schoolyard hustle to the street corner in his neighborhood, and one day, made a life-changing choice. At age fifteen, Marcus and his friends stole a car, which landed Marcus an eight-year prison sentence.

The road has been rough, but today Marcus is an entrepreneur once again, the CEO of Flikshop, and an advocate for helping formerly incarcerated people.

about marcus

Marcus was born and raised between Washington, DC and Prince George’s County, Maryland, where he spent his formative years. Growing up, Marcus’ family was not well off, and money was always tight. In reflecting on his childhood, Marcus remembers Jordans. “My mother’s rule was that she would not pay more than $50 for a pair of shoes, and during my era, Jordans meant everything to teenage boys.” Marcus recalled. Those shoes were a status symbol in his neighborhood. Although none of his neighbors were wealthy, a few of them had gotten a pair of Jordans on special occasions. They allowed children from all walks of life to embody the might of Michael Jordan and all the suave he represented. For kids from Marcus’ neighborhood, these shoes allowed them to hope for better and enjoy a brief respite from the harsh realities of daily life. They were the style. They were the “in” thing. They screamed to the world that you meant something; you were important.

Marcus’ family could not afford to buy Jordans or any other luxury items. This was hard for Marcus. He constantly compared himself to others and chased the idea of being like the other kids on his block. To keep up, Marcus sold candy on the school bus, making ten cents on each sale. His business was lucrative, but he still envied many of his peers. Marcus was intensely attracted to their luxury lifestyle–the cars, large groups of friends, and the female attention they received. However, the people he envied obtained their high status and money through drug dealing. And ultimately, Marcus got mixed up with this crowd.

One night, on an impulse, Marcus and his new friends stole a car from a mall parking lot. Feeling guilty, they returned the vehicle to a “No Parking” zone. They kept the credit cards they found, thinking any money spent would be reimbursed when the cards were reported lost. Using the stolen credit cards, Marcus tried to buy some of the things he desperately wanted as a child. However, he was arrested when a suspicious store clerk called the police.

Unfortunately, police brutality was pretty ordinary in Marcus’ neighborhood. He grew up watching police officers tackle people he had known for years and send them to prison. He was completely desensitized to the police and was not afraid when he was arrested. Marcus knew so many people who had been arrested and figured this would be no big deal. Initially, his greatest fear was that his mother would find out.

But then, things began to get serious. Marcus, barely fifteen, attended all of his court hearings with his mom, many members of his family, and even some of his classmates from school. According to Marcus, one day he was learning about “mitochondria” in Biology; the next day, he was looking up “arraignment” in the dictionary. Marcus, closer to puberty than to adulthood, was charged as an adult and sentenced to eight years in prison.

At first, Marcus was nonchalant about his situation. He thought that his mom would be able to get him out, in the same way she could talk him out of trouble with the school principal. But this didn’t happen.

In prison, Marcus began doing many of the same things he did at home, like playing spades and basketball. The people he met in prison mirrored the people from his neighborhood. It wasn’t until he spoke with someone who had been in prison for thirty-one years that he realized the full extent of his sentence: he would be in prison for the next eight years. This realization hit him like a truck. Two years into his sentence, Marcus became angry and hardened. His outlook darkened and he sought out trouble, but his mother pulled him out of this dark place.

Every day, Marcus’ mother sent a photo or a letter. Marcus jokes that his mom was “Instagram before Instagram.” Daily, the commanding officer came by everyone’s cell and always stopped to hand a letter or package to Marcus. The steady stream of notes and photos was a constant reminder that he was loved and someone was waiting for him on the other side of the prison walls. Marcus’ mother sent photos of everything you could imagine. Of course, there were pictures of the family and friends, but also what they ate for dinner, their new cars, and remodeling work done on the house. Although it is common to take photos of food and daily life now, during the time of Marcus’ sentence, it was considered strange. His mother took her camera with her everywhere. These small, seemingly trivial details were a lifeline for Marcus in prison and kept him connected to a life outside.

While in prison, the letters from Marcus’ mother became a source of joy not only for Marcus, but for other incarcerated people. His friends congratulated him when his nieces and nephews were born; they learned about his family and celebrated birthdays and milestones. Marcus’ mom’s letters and photos carried him through his sentence, fostering hope in his peers along the way.

Marcus was released after finishing his eight-year sentence. He remembers the day his mother came to pick him up. There were so many things he wanted to say, but the car ride was silent. His mother’s first order of business was to get him a coat, so they went to the mall. This was Marcus’ first time interacting with people who were not his fellow inmates. He found it overwhelming and realized that his re-entry would be more complicated than expected.

After being released, Marcus submitted forty-one job applications before landing his first interview at a paint store. Background checks were a huge barrier. Every job application had a glaring question: Have you ever been convicted of a felony? Marcus was required to check the box. But on the forty-second application, the familiar check the box question was worded slightly differently. This time, it asked “Have you committed a felony in the last seven years?” Marcus, elated, did not have to check that box, and he ended up getting the job. After some time working, his entrepreneurial spirit came to life again. He saw an opportunity for him to make money brokering deals between professional painters and homeowners seeking to remodel. He did this for a few years, married, and had his first of three children.

After being out of prison for a few years, an old friend asked him to send photos to prison, as Marcus’ mom used to do for him. This gave Marcus the idea for his company: Flikshop. Marcus used the money he had earned from his paint brokering and construction business to found the company. He learned along the way how to build and grow a startup business. Marcus attributes part of his success to having tough skin, which he developed during his incarceration. It was hard to raise money, and at first, investors rejected him and his idea. But he pressed forward. Because of his perseverance, Flikshop has sent over 500,000 photos to prisons across the country to over 100,000 people. One of his most notable investors is John Legend, via his philanthropic organization FREEAMERICA.

Fast forward to today, Marcus believes there is much to be done to change the narrative around people with felony records. He hopes to continue to advocate for formerly incarcerated people. While Marcus was lucky to receive letters from his mother almost every day, the majority of incarcerated people do not receive any mail. Instead, the commanding officer’s walk past their cell with letters and other deliveries is a constant reminder that they are alone. Marcus wants to improve the support systems for inmates so they can leave prison with hope for rehabilitation.

When we asked Marcus what advice he would give he shared that he believes “change starts at the dinner table.” Talking about the criminal justice system with our families helps deconstruct bias toward people involved in the system. For people who have been through the justice system, he recommends leaning on friends and family, and seeking out organizations dedicated to helping people integrate into society. Most of all, he encourages us to never stop dreaming and working to achieve our goals.

“Don’t be afraid to jump out of the window and build your parachute on the way down.”

What are you waiting for?

It’s time to leave the past behind. Use our tool to quickly check if you have records that are eligible for expungement today!

Find out if you’re eligible in under 3 minutes.

This story is part of our #1in3 campaign, a project to end the stigma and raise awareness of how common it is to have a criminal record.

1 in 3 Americans has a criminal record, which is a lot more common than people think. No one expects to be involved in the justice system, but it can happen to anyone. People of all ages, backgrounds, genders, and income-levels are involved in the justice system. Their pathways vary, but the barriers of a record affect them all. Our hope is that by sharing their portraits and telling their stories, we can change the way people think about people with records and appreciate them for all they have overcome.